Organisational structure – indispensable for companies

So, you have just started your own company. The concept is in place, the starting capital is there, and your employees are highly motivated. However, somehow the initial spark turns out to be smaller than you’d hoped, and the business isn’t taking off. What is missing? You may have forgotten to create an organisational plan. Like any other type of organisation, companies need a clear structure. This is the only way for all parties to know where they stand within the company, what they are responsible for, and who has what authority to issue directives. What is the best structure for your company?

Organisational structure: a definition

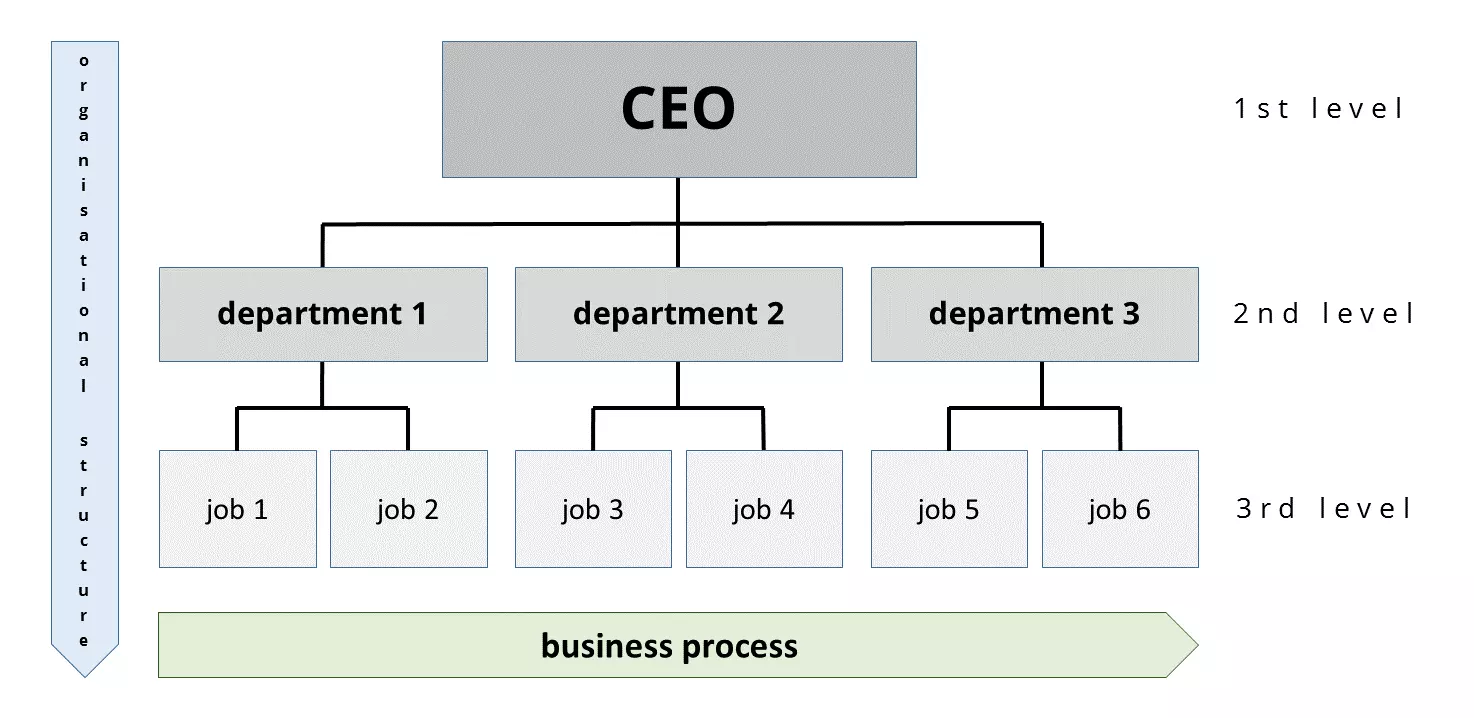

The term “organisational structure” originates from organisational theory and refers to the hierarchical framework that defines the internal division of labour within the company (but the term is also used in the context of other organisations like authorities and NGOs). An organisational plan serves to structure a company according to its individual goals (e.g. increasing production, safeguarding the future, growth) by clarifying them:

- Which jobs and departments exist in the company

- What responsibilities and what authority to issue directive they have

- How the network of relationships between them is formed

- What the vertical flow of information and commands looks like

The organisational structure therefore creates a rough framework for fulfilling tasks in the company and a basis for any standard procedures and routines in everyday working life. These are then concretised and complemented by additional instruments (namely planning and management), as well as by the activities of the participants in practice. Depending on the objectives pursued by the company, an organisational plan can look very different.

In the scientific theory of organisational theory, a distinction is made between structural and procedural organisation. The former determines who has to do what and with whose support. The latter, on the other hand, describes the when, where, and how of these activities.

How important is the organisational structure for a company?

Companies need a clear structure in order to function smoothly and to grow at the same time. Without it, there is no clear focus, neither for the management nor for the employees. No one knows exactly what falls within their area of responsibility and to whom they have to report. This causes confusion and stress – and conflicts over responsibilities are almost inevitable. The consequence is lack of coordination and slow decision-making processes that can have a long-term effect on the economic efficiency of a company.

A well thought-out organisational structure, which defines command chains, control spans, and communication channels in a comprehensible way, helps to align all energies with the corporate goals. This can be achieved, for example, by clarifying the chain value, providing an overview of the work areas, and even reducing organisational costs. It also helps new employees to orient themselves within the company, identify superiors and subordinates, and understand the big picture and their career opportunities. A clear organisational structure therefore contributes to job satisfaction and the employee’s sense of security. For this reason, it is often communicated as an organisational chart, e.g. in the recruiting area on the company’s website.

Thanks to its wide range of programs, Microsoft 365 is guaranteed to lighten your workload. Get the package that best suits your needs now from IONOS!

Organisational structure of a company: the design process

Designing the right organisational structure and presenting it in a clear organisational chart is not that easy. The biggest difficulty is to create a solid and reliable structure in spite of complex and dynamic environments. In order to do justice to this task, you first need to know what such an organisational chart consists of:

- Structure elements: All the action units to which the previous tasks in the company are distributed; these include the smallest unit (the job), the body (a body with authority to issue directives), the department (a combination of several units under the direction of one body), supporting departments, as well as teams and committees, which are usually deployed for a limited time to handle complex projects.

- Structure relationships: The network of relationships between all the above-mentioned organisational elements.

- Piping systems: Graphic elements like boxes, lines, and arrows that visually illustrate the order and pathways of instructions.

The organisational plan design process is now divided into two steps:

- During the task analysis you identify all goals of your company, translate them into the main company tasks, and break them down into subtasks. The classification can be according to performance (e.g. physical/mental), object (e.g. a product), earmarking (primary or secondary tasks), phases in the management process, or the rank in the hierarchy.

- The synthesis of tasks represents the actual organisational activity for you as the founder of the company. Here, you take the subtasks determined in task analysis and combine them into meaningful task complexes that are assigned to the corresponding jobs. The greatest challenge here is to make optimum use of existing resources and ensure smooth cooperation between all structure elements.

How do you differentiate between different forms of company organisational structures?

The following six components are used to differentiate between the usual forms of organisational plan in an enterprise:

- Chain of command (long or short): The basic component of the organisational structure; a chain of command means an unbroken line of authority between the top management and the employees at the lowest level. It specifies who is to report to whom (keyword: reporting).

- Control span (wide or narrow): The more subordinates a supervisor can or must effectively manage, the further the control span of an organisational plan.

- Centralisation (centralised or decentralised): This component describes whether the decision-making in the company takes place at a central point (in the management) or decentralised (in consultation with the employees). The latter variant is considered more democratic, but can also slow down the decision-making process.

- Specialisation (specialised or differentiated): Also referred to as division of labour; describes the degree to which tasks in a company are broken down into subtasks and divided into individual jobs. With a high degree of specialisation, employees can become experts in their field and work more productively. A low level of specialisation encourages the training of flexible, all-round talent.

- Formalisation (formal or informal): In formal organisational structures, jobs and processes are strongly regulated and standardised independently of the executing person. An informal organisational structure, in turn, gives the individual more freedom to shape their work based on their preferences, abilities, and performance. This enables employees to look beyond their proverbial horizons and to orient and educate themselves in other departments.

- Department formation (rigid or loose): In English, the term departmentalisation means the process of grouping jobs together to realise joint projects. Rigid department formation therefore occurs when all departments are autonomous and hardly interact with each other, whilst a loose concept strongly promotes collaboration.

The individual combination of these components results in different forms of organisational structures, which can basically be arranged on a spectrum between “mechanistic” and “organic.”

- Mechanistic: The term mechanistic refers to the traditional approaches to organisational structure, which include the functional and divisional organisational structure as well as the matrix organisation. These kinds of organisational structure are characterised by a tendency towards a fixed chain of command, narrow control spans, and a high degree of centralisation. Jobs and departments are comparatively highly specialised, formalised, and rigidly subdivided.

- Organic: The organic part of the spectrum includes various innovative and experimental organisational structures, which in summary are often referred to as “flat hierarchies.” The chain of command is less strict, but control spans remain. In the components centralisation, specialisation, formalisation, and departmentalisation, these concepts are also in contrast to the mechanistic part of the spectrum.

What are the most common organisational structure examples?

In organisational theory there is a selection of structural archetypes that are frequently used. Bear in mind, however, that many companies tend to use hybrid models that combine the characteristics of different organisational structures.

Functional organisational structure

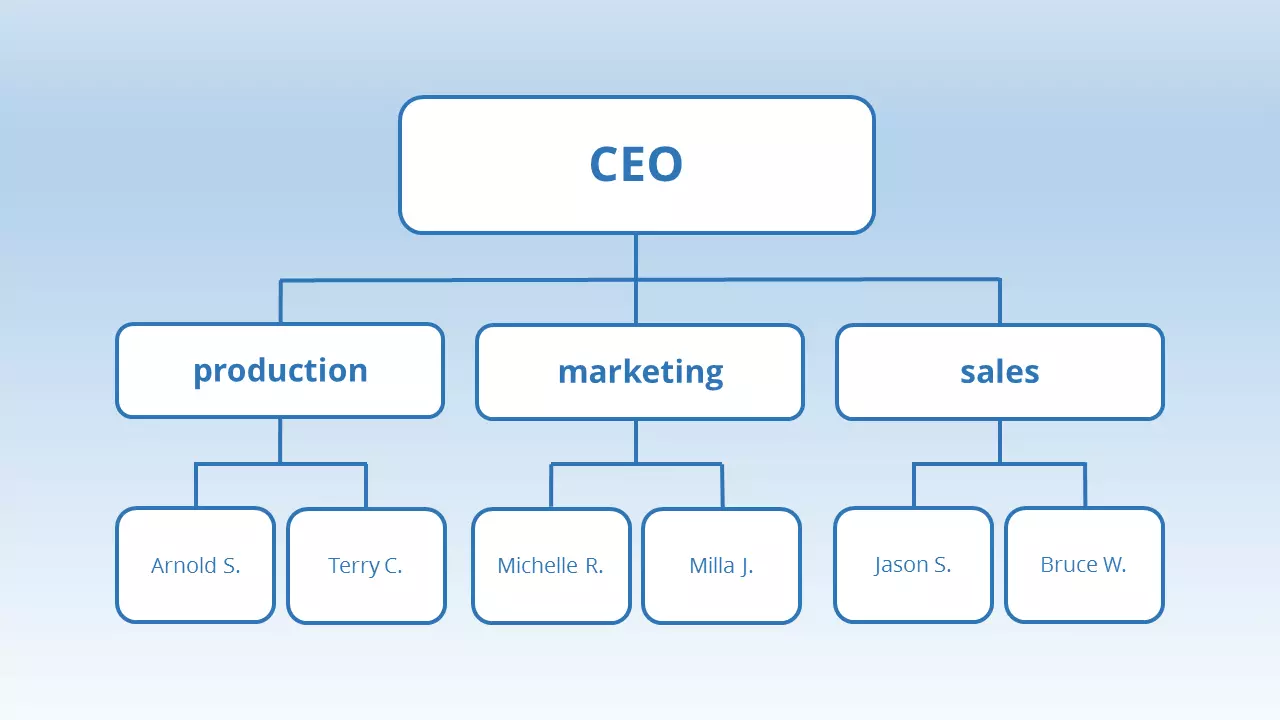

The oldest and most widespread form of organisational structure divides a company into general, strictly differentiated job functions. This means, for example, that all marketers are combined in one marketing department, all HR managers in the human resources department, etc.

The advantages of this easily scalable concept are that employees can specialise in their respective area and thus work more efficiently. Clear areas of competence and responsibility prevent activities like accounting from duplicating in the various departments (this is referred to as “redundancies”). At the same time, the functional structure allows quick decision-making. This makes it particularly suitable for smaller companies that produce a rather narrow range of standardised goods in large numbers and at low cost.

Disadvantages are the potential barriers that can arise between the various functional areas if such a rigid division is formed. The more a department works for itself, the worse its ability to communicate and its understanding of other departments is – sometimes also referred to as “departmental selfishness”, which can manifest itself in conflicting interests, conflicts and, in the long term, also in inhibited productivity. The lack of orientation towards a specific market, target group, or product and the high degree of standardisation and formalisation also limit any potential for innovation.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Clear responsibilities Easily scalable Strong specialisation amongst employees High working efficiency Prevention of redundancies Fast decision-making | Potential barriers between functional areas Lack of communication and cooperation Lack of understanding of other job functions Risk of sectoral selfishness and conflicts Low product, target group, and market orientation Limited innovation potential |

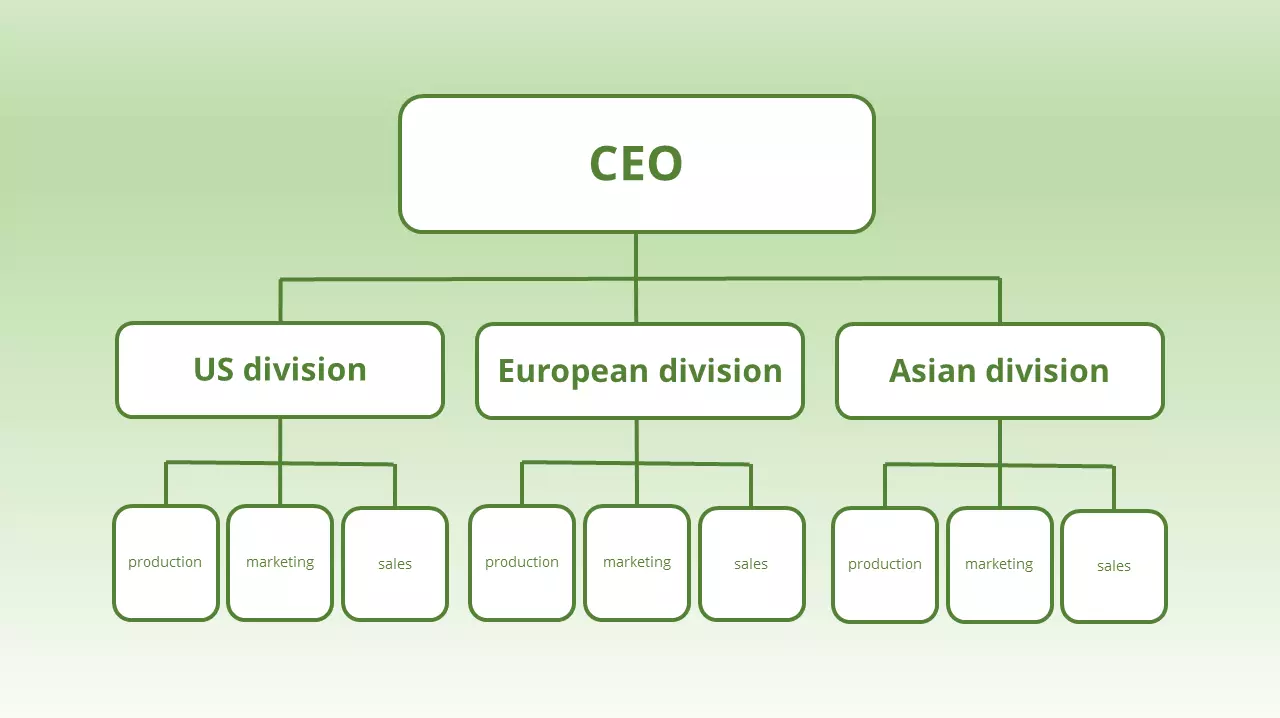

Divisional organisational structure

Divisional organisational structures, also known as “divisional” or “business area organisation” become relevant whenever a company grows and must be structured in a more differentiated way. The subdivision then usually takes place according to the following work areas:

- Products/services

- Target groups/markets

- Regions/sales areas

These structural elements, also known as “divisions,” each have separate functional areas, i.e. their own production, marketing, and sales departments.

In this highly adaptable structure, each department can concentrate on its respective field of activity and thus work faster, more strategically, and in a more coordinated fashion. The resulting autonomy leads to greater employee motivation. At the same time, the more differentiated allocation makes it possible to make individual business activities more transparent and to measure and evaluate their performance precisely. For these reasons, divisional organisational structures can be found primarily in larger companies that offer a wide range of specialised products and services for various sales markets. A subdivision according to regions is particularly suitable for internationally active companies. In these cases, decision-making is usually decentralised.

The fact that divisional structures are more differentiated and therefore require more specialised managers is one of the reasons why implementation is associated with higher costs and greater coordination effort. If the individual departments work autonomously or if they are far apart geographically, there is also the threat of divisional selfishness and the duplication of business activities. In the worst case, this can lead to a discrepancy between the goals of the divisions and the actual core goals of the company.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Very flexible Concentrating on the respective division strategies Market proximity and target group orientation High motivation through greater autonomy More transparency enables a more precise assessment of success | Higher coordination and management effort Limited communication due to (geographical) separation Risk of departmental selfishness Possible emergence of redundancies Risk of discrepancy between corporate and divisional targets |

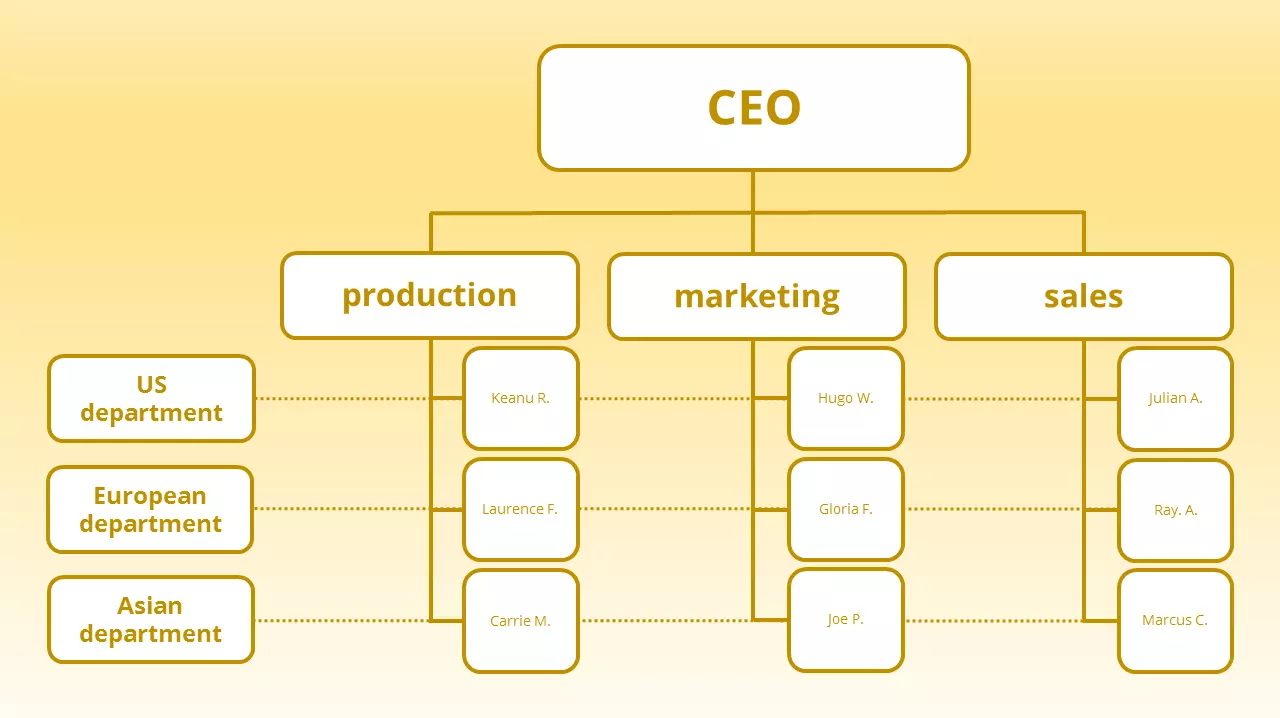

Matrix organisation

This organisational structure combines the advantages of functional and diversional models and packages them in a three-dimensional matrix. It divides jobs and departments first by function and then by division. The applicable authority to issue directives is divided into two independent, equal dimensions. This means that all employees are in two instructional relationships at the same time – with the department head responsible for them and the respective product manager. In the organisational chart, these relationships are illustrated by means of vertical and horizontal lines.

The strength of the matrix organisation lies in the fact that it can be flexibly adapted to better cope with fluctuations in capacity utilisation in the company. The shorter communication channels and the availability of specialised contacts at all times give better dynamics to decision-making and transmitting information. Due to its complexity, however, the matrix organisation is mainly used by large, internationally active companies like Starbucks and in project-oriented industries like construction and vehicle development.

It is also this complexity that not only ensures high planning and implementation costs, but can also cause confusion amongst employees. Potential points of contention here are dual management: cross-fertilisation of responsibility areas can lead to conflicts of competence and make communication, decision-making, and the assessment of performance more difficult. For this reason, many companies in practice appoint just a single authorised person (usually the function-related department manager), who temporarily assigns tasks to subordinates in the respective product areas.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Combines the advantages of the functional and divisional organisational structure Higher flexibility Better at coping with fluctuations in capacity utilisation More dynamic communication and faster information transfer Broad democratic decision-making | High planning and implementation costs Complexity can lead to confusion and conflict High communication overhead Difficult to attribute successes and failures |

Flat hierarchies

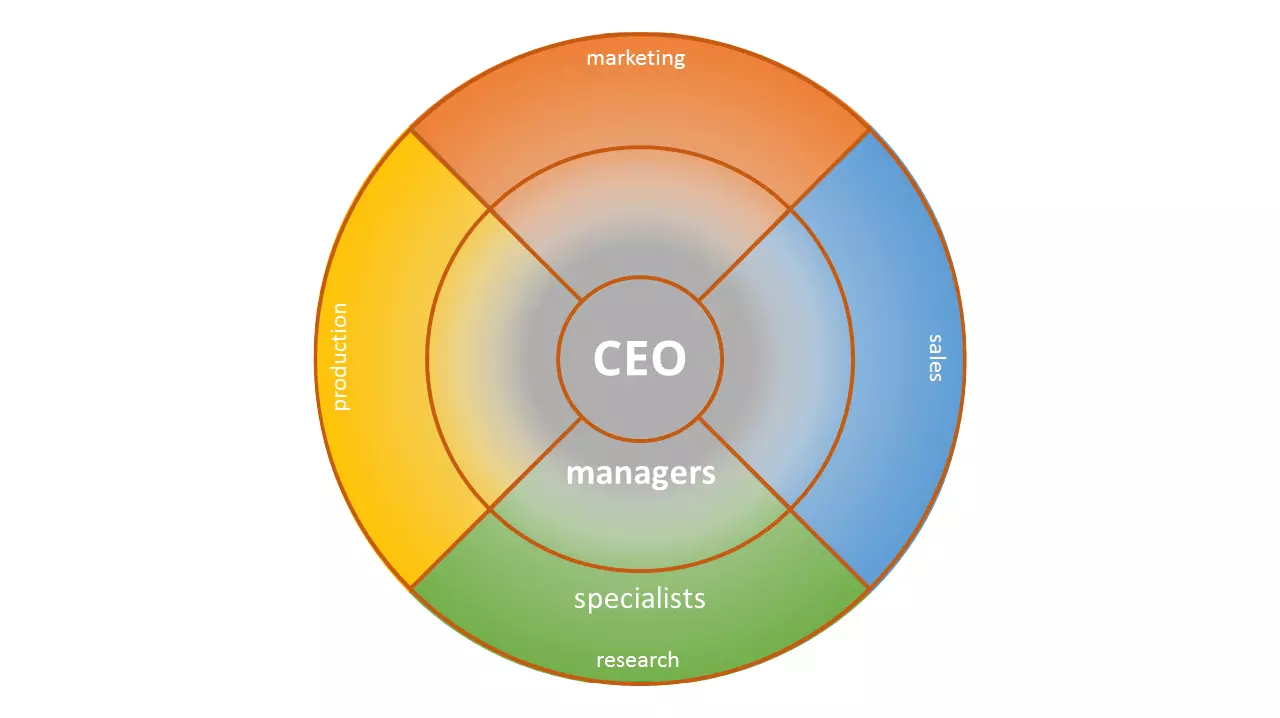

The working world’s further development has produced numerous innovative and experimental forms of organisational structures that compete with traditional concepts. Team-based structures as well as networks and holdings should be oriented strongly towards the requirements of digitisation and the modern working world and in return turn away from classical chains of command. Corresponding concepts are usually summarised under the term “flat hierarchies” and presented, for example, as a circle (e.g. in a circular organisational structure):

Although there is a hierarchy in this kind of organisational chart, management is not represented at the top, but instead in the middle of the organisation. This implies the ideology that the CEO intervenes less directly in the work of employees and instead communicates their business visions from the inside out. There are only a few levels of middle management, so individual department heads are responsible for more employees but the chains of command are correspondingly shorter.

Flat hierarchies therefore increasingly rely on the initiative and individual responsibility of employees. At the same time, they make it possible to provide feedback directly to a relevant contact person instead of having to pass on their ideas through the traditional, lengthy bureaucratic route to the top. Whilst traditional concepts provide for a relatively strong separation of semiautonomous departments, the limits are less strict for flat hierarchies.

This allows more flexibility in the work design and is intended to increase employee motivation. Flat hierarchies are particularly popular in smaller, younger companies like start-ups. As a company grows out of this stage, however, the tendency is to counter the increasing complexity of business activities with more departments and a longer chain of command. Experience shows that just a few of these companies maintain their original organisational structures; examples include the video game developer Valve Corporation and the web hosting service GitHub Inc.

The biggest disadvantage of a lax hierarchical structure is that it is not equally appealing to all employees, since authority to issue directives and responsibilities are not always clear. Therefore, it can be difficult for a new employee to recognise their exact place in the company at the beginning. Most organisational structures of this kind have not been tried and tested for very long – so original concepts are practically always a stab in the dark for you as a founder.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Adaptable to the conditions of digitisation and the modern working world Great flexibility in design Communication and cooperation at “eye level” Short chains of command More dynamic feedback culture More flexibility in work design Greater motivation and greater commitment on part of employees | Often cannot keep up with the increasing complexity of an organisation Unclear powers of instruction and areas of responsibility Potential confusion among employees Experimental character – a lot of trial and error |

Summary: Is there such thing as the “right” company organisational structure?

To be successful with your company, you must first determine an organisational plan that best fits your goals. Which organisational structure is the best – whether it’s a traditional/mechanistic or modern/organic one – is still up for debate.

If you want to clear areas of responsibility and stringency, the functional model is probably best for you. However, if you have a wide range of specialised goods and you are also active in the international market, you should consider a hybrid concept and combine a functional structure with a divisional one to form a matrix organisation. But this isn’t the end of the story: Flat hierarchies and equal team models are on the rise, because they allow closer communication and cooperation between employees and promote motivation.

At the end of the day, there is no perfect solution – every good organisational structure always represents a compromise between a fixed structure (integration) and the deeply dynamic company environment (differentiation).

Please note the legal disclaimer relating to this article.