Declaration of intent–what’s behind it?

Every time you enter into a legal transaction, you must express your intention to cooperate: “I would like to buy this car!” or: “I would like to commit to this rental agreement!” This might sound banal at first, but it is the deciding factor in civil law - without an orderly declaration of intent, no contract can be signed, and no legal transaction can be successfully completed.

What is a declaration of intent?

The intention to enter legal relations is a doctrine used in contract law. Once an offer has been accepted, there is an agreement, but not necessarily a contract. So that a legal transaction can be completed, there must be one or several declarations of intent. In other words, a declaration of intent is an expression that should bring about a legal transaction. Only a person of legal capacity can enter a binding declaration of intent.

Every contract requires at least one declaration of intent – without this, no legal transaction can take place. The number of involved declarations – whether it’s just one person expressing their wishes, or two people are involved – depends on whether a one-sided or two-sided legal transaction is to take place. With purchase or rental agreements, for example, two people are always involved: One side makes an offer, the other accepts it. In this case, both parties must effectively express their intention to enter a legal relation – with an emphasis on “effective.” Not every declaration of one’s intentions acts as an effective declaration of intent.

The most important thing is that a statement is made. Without this, you can’t complete a legal transaction, whether verbal or written. In addition, the receiver must also receive the declaration of intent, unless this step isn’t necessary. No obstacles should stand in the way of you making an effective declaration.

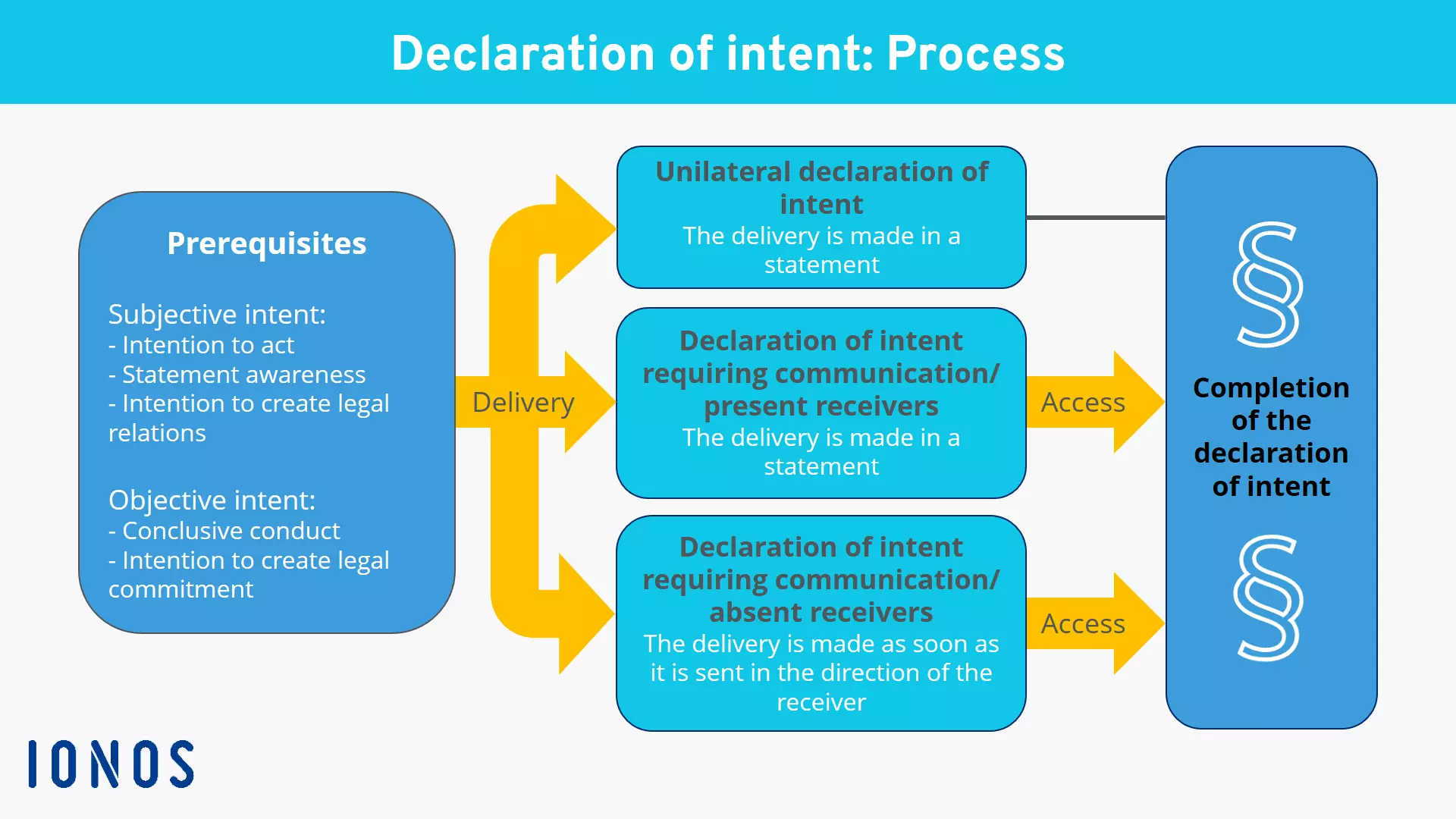

The two types of declaration of intent

We can differentiate between two types of declaration of intent. The most common type is the unilateral declaration of intent. When you make a statement that expresses intent to enter legal obligations, a second party is usually involved. For example, it can involve direct contact between two parties.

Even if the recipient is absent, a declaration of intent can still be expressed. If, for example, a letter of correspondence is sent, the statement is only valid once the recipient receives it and it’s irrelevant whether the recipient is aware of it. Most importantly, the recipient must be given the opportunity to read the declaration of intent – so it is within their sphere of influence.

The second type is a declaration of intent requiring communication. For this to be valid, it’s enough that the declaration is submitted. It’s not necessary that someone becomes aware of it. The most common example of this is a will or testament. Whether it is sent to someone or not, it is still valid.

Components of a declaration of intent

Every declaration of intent is made up of two principles:

- Subjective intent

- Objective intent

Subjective intent

Subjective intent is based on the state of mind of the subject, i.e. the person declaring their intent. Three elements define this form of intent. For one, a desire to act is required, i.e. a known inner intent must exist to do something or have something done. This also means that unconscious people (including those sleeping) cannot provide a valid declaration of intent.

In addition, the subject must be aware that they are making the statement. This means that they want to express their desire to act. According to this, they must be aware that their actions will lead to a legal transaction, for example, the signing of a contract. After all, the subject must also have an intent to create legal relations. This relates to the conclusion of a concrete legal transaction, including its related consequences.

The example of a wine auction is common among lawyers. In this example, someone greets their friend with a wave. The auctioneer notes this as an offer, whereby the man has auctioned an expensive wine. However, he wasn’t aware that he would be giving a declaration of intent in this way in this specific situation. Although the intention of stating something of legal consequence is missing, the auction participant is entering a contract, because he should have been aware of the meaning of the hand signal in the given situation. He may appeal his declaration of intent but may be required to pay compensation.

These elements are all directed at the subject and his intentions. To make a declaration of intent valid, it must however also be outwardly expressed. And the explanation must be subjectively understandable.

Objective intent

Objective intent is fulfilled when the declaration is explicitly made in written or verbal form or where this is implied. This means that a person’s implied behaviour can serve as an explanation for a person’s intent. For example, if you board a train, you’ve implied that you want to travel on this train. An objective third person can observe that you’ve accepted the legal consequences of your action. Utterances made, for example with the threat of violence, do not count.

Silence is a special case in implied intent. In most cases, not acting does not count as a declaration of intent. This changes in the case of contractual deadlines: If you don’t reply within a given timeframe, the agreement is deemed concluded.

Beyond this, the intention to create a legal commitment constitutes a valid declaration of intent. The subject must signal that he wants to enter the legal transaction, for example by signing a contract. However, this does not apply to recommendations or favours. The side that offers to help does not want to enter a legal agreement and does not want to be held accountable for the consequences of their actions. When it comes to the intention to create a legal commitment, it must be clear to an objective third party that the statement is correctly interpreted. If not, the subject was too ambiguous in their statement

How can a declaration of intent be made?

To make a declaration of intent valid, two conditions must be fulfilled: It must be made in an effective way, and it must (if required) effectively register with the recipient.

Effectively making a declaration of intent

A declaration of intent begins with a deliberate and voluntary expression. If we’re talking about a unilateral declaration of intent, the process is already complete.

A declaration of intent that requires communication is different. In this case, the statement must be directed at the recipient. In addition, you must differentiate between recipients who are present and absent. A person that’s present will instantly receive the declaration of intent, while for those absent the transaction is only successful once it has followed a delivery process. For example, by placing a letter into the letterbox, the transaction to those absent is regarded as complete.

There are two problems that can arise with a declaration of intent that requires communication:

Incidental information: In this case, one party provides a declaration of intent, and is made aware of something intended for them, just ahead of time. The declaration of intent shouldn’t have reached the recipient at this stage. This is the case, for example, if a landlord overhears a conversation between two tenants, where one states: “I have a new job. In two months, I’ll be terminating my lease.” Although this statement was intended for the landlord, it shouldn’t have reached him yet. He has only overheard the statement by chance. In this case, the declaration of intent is not regarded as received, since the tenant didn’t willingly bring it to the landlord’s attention.

Lost declaration of intent: It’s possible that a person formulates a written declaration of intent and signs it without bringing it to the attention of its recipient. Should a third person get involved with the declaration of intent, without the knowledge and against the will of the declaring party, then its validity is not granted. An example: Business owner B leaves a completed order form for a new dishwasher on her desk. Her secretary assumes that the order should be placed as soon as possible and sends it off.

The declaring party (= B) has not made a declaration of intent with the intention to act. The declaration was not submitted. But in legal speak, there is another opinion: If B provoked this behaviour by way of negligence, then the recipient can deem the transaction as binding.

A declaration of intent must be effective

A declaration of intent requiring communication must be received, otherwise, it is not valid. The general rule is: A declaration of intent becomes valid as soon as the recipient receives it. In the case of an absent recipient, it becomes valid no sooner or at the same time as it is revoked.

For example, if you send your declaration of intent by post, and then you realise that you’ve made a mistake, you can revoke it quickly yourself before the recipient receives the letter. An extended revocation period – something consumers are used to – can also be agreed upon in advance.

A declaration of intent will also stay valid should the declaring party die after making their statement or losing their legal capacity.

Nullifying a declaration of intent

There are various grounds for invalidity that can nullify a declaration of intent:

- Legal incapacity: According to UK law, if you do not have legal competence, you cannot make a declaration of intent.

- Joke explanation: A declaration of intent is not valid if it’s intended as a joke. It’s also not valid if the recipient isn’t aware that it’s a joke. However, the declarant must be prepared to refund any costs that occurred due to the misunderstanding. Should the recipient acknowledge the joke, then the declaration of intent is completely off the table.

- Mental reservation: If you keep to yourself that the declaration should not be taken seriously, and if this reservation is not recognised, then the declaration of intent is still valid. However, if the recipient is aware of this reservation, then the declaration is invalid.

- Fictitious transaction: If you make a declaration of intent under false pretences, whereby the contractual partner is in the know of this (for example to deceive a third party), the declaration is also deemed invalid.

Contestability of a declaration of intent

Misunderstandings don’t automatically make a declaration of intent invalid, but they do provide reasons to appeal.

- Content error: If the contents of a contract are misunderstood and the declaration has already become legally binding, then it is still valid, but it can be appealed. Example: misunderstanding a foreign word.

- Explanation error: If the explanation of the declaration unknowingly deviates from the actual declaration, then it can be appealed. Example: a typo.

- Transmission error: If an error occurred while it was being transmitted electronically and the actual declaration is falsified, it can be appealed. Example: a mistake in the electronic management system.

- Property error: If assumptions are mistakably made about certain attributes surrounding the item in question or the contractual partner, then the declaration of intent can be appealed. Example: jewellery made of brass instead of gold.

- Intentional deception: Should the declaration of intent be created in the context of deliberate or malicious deception, it can be appealed. Example: a used car that’s sold as “accident-free” although the seller had a traffic accident in the car.

What can’t be appealed is a so-called motive error: While forming the declaration, the declaring party is basing his assumptions on a false motive, which informs the declaration. In this case, the declaring statement cannot be appealed. Example: wrongly assuming the cheapest price.

Declaration of intent examples

The best way to understand a declaration of intent is by way of examples. We’ll introduce you to various situations that might arise in the delivery of the declaration based on two types of declaration of intent (declaration of intent requiring communication/unilateral declaration of intent).

Example 1: Unilateral declaration of intent – testament

A unilateral declaration of intent is not that common. It can include:

- Competitions (the promise of a reward for a specific action or activity)

- Foundations (a document that explains that assets can benefit a specific goal of the foundation)

- Testament or will

In this example, we assume that you want to create a testament to plan the distribution of assets in a timely manner. In the UK, the two main will types are the written will and the holographic handwritten will. The written will must bear the testator’s signature at the bottom and the signature of at least two attesting witnesses. The holographic will must be witnessed in the UK and there must be proof that the testator created the will themselves. The will has to be written entirely by the testator’s own hand and must be signed.

By writing a testament, you fulfil all requirements for a declaration of intent. You have the intention to bequeath your assets. The intention of doing so with an understanding of legal consequences is demonstrated by recording it in the testament. And your intent to enter legal relations is also provided: In death, you would like the piece of legal writing in question to be distributed. Subjectively, your intent to act is clearly understandable, and as long as you stick to all legal requirements, there is little potential for misunderstandings. The intention to enter legal relations is also clearly noticeable by a third party, for example, an executor: It is clear, that the document forms a legally binding agreement.

A testament is directed at one or several people, who become part of the legal transaction in the process. Contrary to other declarations of intent, though, a will does not have to reach someone to become valid. Once you have signed the document, it’s valid. Even if you die directly after signing it and no one else but you saw the testament. There are no grounds for invalidity.

Example 2: Declaration of intent requiring communication – shopping

Every day we enter a declaration of intent which involves legal transactions – for example, when shopping for breakfast rolls at the bakery. This involves a declaration of intent that requires communication. But first, you’re still forming your declaration: you would like to buy some breakfast rolls. Your intention to act is therefore clear. You also have an intention of doing so with legal consequences, as well as to enter legal relations. You can bring this across in different ways. Since the contractual partner in question is the person on the opposite side of the counter and is present, a statement in writing isn’t necessary.

Generally speaking, orders are placed verbally: “Four rolls and two croissants, please!” It’s even possible to (partially) communicate nonverbally: by pointing to the product and holding up the number of fingers relating to your order. The other person can now interpret your intent. The price tag next to the baked goods informs you of the consequences of the legal transaction. A misunderstanding can arise if the items are not correctly labelled – for example, if a rye roll turns out to be a spelt roll when you bite into it, then this is a content error. In this case, you can, theoretically, appeal the declaration of intent.

Example 3: Declaration of intent requiring communication – rentals

Contrary to buying bread, renting or letting an apartment is a very formal affair. Contracts are signed, either directly at the site with all involved contractual partners, or the rental agreement is sent in the mail. In this case, you’re dealing with a declaration of intent requiring communication between absentees.

Here, it’s clear that both sides will submit their declarations of intent – not only the tenant but the landlord also expresses his intent. If you’re a prospective tenant and you receive the contract in the mail, then this will most likely already have the landlord’s signature on it. In doing so, the landlord has expressed their intent that they want to offer you the apartment based on the agreed-upon conditions, which are stated in the contract. With your signature, you’re declaring your intent. Now, you only have to send it off to the recipient.

However, the declaration of intent only becomes valid once it’s been received by the tenant. It’s also important that the tenant receives the signed copy. It’s enough that this is in their sphere of influence. Once the post service has signed for the delivery and the envelope is accepted by a secretary or clerk, it’s possible for the tenant to read the contract without any problems. It’s different if the mailman throws in the letter on a Saturday, as you can’t expect the tenant to check his mail at the office on the weekend. That’s why the declaration of intent is regarded as valid only from the following Monday.

In this case, the mail can be regarded as the messenger of the statement, transmitting the order for the customer. If the receiver were to commission another mail carrier to pick up the declaration, then this is described as the receiver of the statement. In this case, the statement is regarded as received if the average transmission time – the average time that the messenger probably needs to deliver something – has run out. The sphere of influence then begins with the receiver of the statement.

Although we’re dealing with a declaration of intent between absentees, the danger of a transmission error is minimal. The messenger of the news is the mail carrier, who hardly has the possibility to falsify the contents of the declaration, as this is a written document inside a sealed envelope. It’s different if the mail carrier were to deliver a verbal declaration. In this case, the mail carrier may unknowingly make a mistake.

But another error may occur and could lead to legal proceedings: Let’s assume that your landlord sends the signed rental agreement to you. Within, it states that the apartment will cost £500 per month. You’re a little confused since you’d always spoken of £600. Happy about the discount, you sign the contract and send it back. However, the landlord has made a mistake by mistyping the monthly amount. Their intent is still to rent the apartment to you at £600 per month. This is a so-called explanation error.

The question now is: Was it clear to you that you’re dealing with an error? For your reply, it’s less important how you interpreted the declaration as how you should have interpreted the declaration. Both good faith and recognised customs come into play here. In the example, the contract negotiations must be considered. Since a concrete rate had always been discussed, you should have known that it was a mistake. The landlord can, therefore, appeal the declaration of intent.

Please note the legal disclaimer relating to this article