Personal Data

The much-discussed GDPR regulates data protection and has been in place since May 2018. The regulation stipulates that it applies to web users in the EU, so if you have any contact with them, it may be a good time to wise up on the GDPR. Its content focuses in particular on personal data, which both legislators and internet users see as highly worthy of protection. On the other hand, numerous business representatives see their ability to keep up in a competitive market, which is significantly based on big data, threatened by the stricter regulations. But what are personal data, and what rights do you have to your own?

Definition: what are personal data exactly?

The term personal data is generally understood as all data and information that provide insights into the identity of a natural person – that is, into a person “made of flesh and blood,” although there is no clear cut legal definition. This view therefore excludes legal entities and corporations, unless the partners and managing directors are the same individual.

Personal data is defined as “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (“data subject”); an identifiable natural person is someone who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity of that natural person”; (original wording from Article 4, paragraph 1 GDPR).

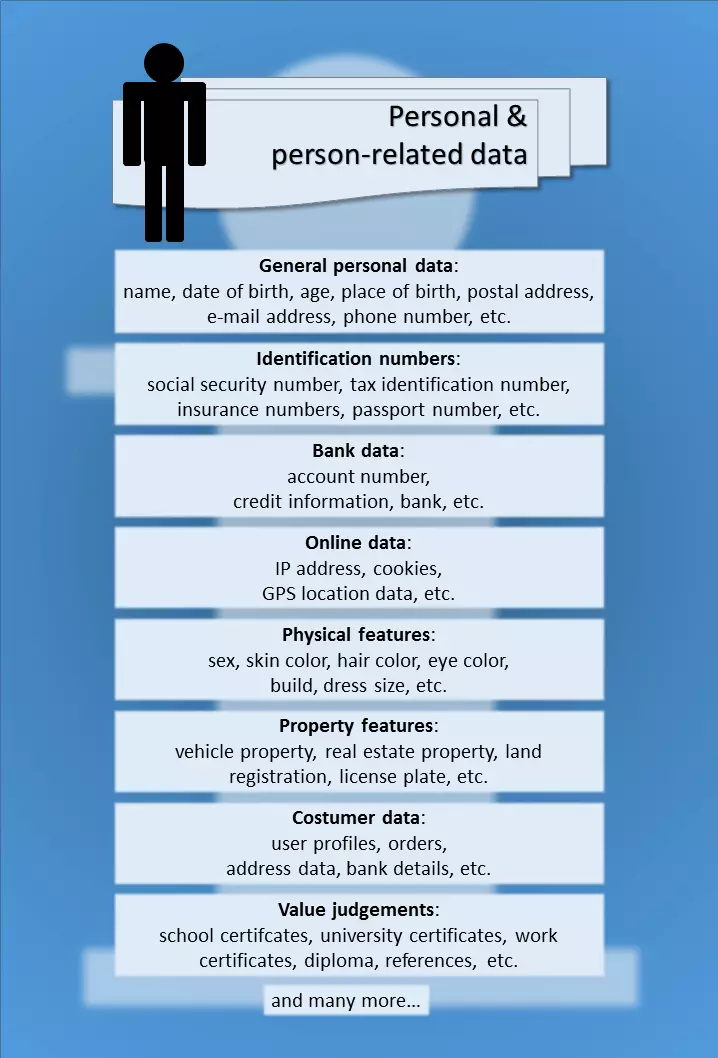

According to this definition, there are many types of personal data, some of which are presented together with examples in the following image. This overview is by no means complete, and just aims to provide a succinct list.

If, on the other hand, the data cannot be assigned to a specific person because it is completely anonymous, no data protection rules need to be followed. The problem arises again with so-called “pseudonym-ised” data, which can also be used to determine a unique reference person if you have the necessary additional information. In case of doubt, the principle of caution always applies. Since it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between personal and non-personal data, you should always start from the former in order to guarantee the protection of potentially private information. For example, data protection authorities assume that even IP addresses belong to personal data, since they can be clearly assigned to the respective internet user through the interaction of access and service providers.

What particular types of personal data are there?

In addition to the examples of personal information already listed, the GDPR also defines “special” personal data relating to natural persons. These include:

- Ethnic and cultural background

- Political, religious and philosophical views

- State of health

- Sexual orientation

- Union membership

- According to article 9 of the GDPR, genetic information (e.g. DNA analyses) and biometric data (e.g. photographs and fingerprints) are also included

Due to the sensitive nature of this information, the relevant privacy regulations are much stricter. Accordingly, processing special categories of personal data is in principle prohibited under Article 9(1) of the GDPR, unless the data subject has expressly consented to having their data processed (a declaration of consent for processing general personal data is not enough). Another way in which personal data may be processed is if there is a legitimate public interest in this information, e.g. in the context of criminal prosecution. While the appointment of a professional data protection officer is normally a matter for consideration by the managing director, it is obligatory for the processing of special personal data.

Why and how must personal data be protected?

It should be common knowledge that large internet companies such as Google and Facebook collect personal data about their users on a large scale. They mostly use these to place individualised advertising and generate economic profits. The data is mainly used for optimising sales and individualising marketing mechanisms.

This is made more difficult, as people are becoming ever more cautious of what they data the disclose online, and fear becoming “transparent people,” represented only by online data profiles. Recurrent cases of data theft and data abuse phishing and the use of Trojans fuel this fear even more. Because the more sensitive information about an individual is circulating, the greater the risk their financial and social information is at.

Data protection regulations therefore make those with heaps of personal data responsible: companies and authorities are legally obliged to guarantee the protection of information about their customers. This implies compliance with the following principles and practices laid out in the GDPR:

- Legality of data processing: The collection, storage, use, and forwarding of personal data to third parties is only permitted with the express consent of the data subject.

- Transparency: Companies and authorities are subject to comprehensive accountability, documentation, and proof. At the request of a data subject, they must provide information on all processing procedures relating to his or her personal data.

- Earmarking: The use of data must be earmarked at all times and must not be arbitrary.

- Data minimisation: Organisations are required to collect only the most necessary data for their purposes and to keep the amount of information stored generally low.

- Correctness of data processing: Stored data must always be correct and up to date and updated if necessary.

- Storage limitation: There is a regular obligation to delete data if it is no longer required for the purpose of an organisation, if it has been stored illegally, or if a predetermined period of limitation has expired.

- Integrity and confidentiality: Companies and authorities must take extensive measures for internal data protection. In addition to the use of encryption programs and security software, this also includes detailed training of employees entrusted with data processing.

Violations of these principles can result in a fine of up to 20 million euros, or up to 4 percent of a company's worldwide annual turnover under Article 83(5) of the GDPR – a rule that provides a financial incentive to comply with the guidelines but still cannot guarantee absolute security for personal data. Data economy is therefore also an effective principle when surfing the internet. Furthermore, it is recommended to delete or at least falsify personal, address, and bank data entered after completing an online purchase. Last but not least, it also makes sense to be aware of your rights towards companies and authorities.

What rights do people whose personal data are collected, stored, and processed have?

The GDPR stipulates three essential rights that people have when their personal data is collected:

Under European law, personal data must in principle be regarded as the property of an individual. In practice, this means that the collection, storage, processing, and forwarding of data is only permitted with the express and active consent of the person in question. An implicit recognition of the data protection practice of an online service is therefore not sufficient. A so-called coupling is also not allowed, in which a company or an authority only releases certain services against consent and leaves the user no free choice.

Under Article 15 of the GDPR, people also have a right of access to the companies and authorities to which they provide their personal data. The Information Commissioner’s Office offers a short, informal sample letter, which can be easily adapted and supplemented with any extra information you want to supply. The following questions are useful to get a good overview of the extent and procedure of data storage:

- Which data is stored about my person?

- Where is this data stored?

- How was this data collected?

- For what purpose were they stored?

- To whom was my data passed on?

Although companies and authorities are obliged by law to provide information, in some cases you have to reckon with unwillingness or even harassment if you want these questions answered. This is where persistence pays off: by invoking your rights, setting a tight deadline, and ultimately threatening to consult the responsible data protection authority, you finally get the certainty that you deserve. And if you do not agree with the way in which data is collected, information is incorrect or outdated, or has even been stored or passed on illegally, you can apply your last right: the right to correct, delete, and block data (Article 15(1e) GDPR).

Click here for important legal disclaimers.