Internet Protocol Version 6 (IPv6)

With the introduction of IPv6, fundamental processes of network communication are changing. The expansion of address room from 32 to 128 bit not only counteracts the increasing shortage of IP addresses; the new standard also makes it possible to uniquely address all devices in a network. Unlike IPv4, version 6 consistently implements the basic idea of IP, the end-to-end principle. We will explain here how it all works.

Try out your VPS for 30 days. If you're not satisfied, we'll fully reimburse you.

What is IPv6?

IPv6 stands for “Internet Protocol Version 6” and represents a standardised process created by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) for the transmission of data packets in computer networks. IPv6, the directed successor of IPv4, together with around 500 other network protocols of the TCP/IP family, forms the basis for internet communications. Central functions of IPv6 are the addressing of network elements over so-called IPv6 addresses as well as routing, or the packet forwarding between subnetworks. For this purpose, IPv6 is based on the network layer (layer 3) of the OSI layer model.

The allocation of IP addresses goes through so-called RIRs (Regional Internet Registries), which are each assigned their own IP address ranges by the IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority). The RIR responsible for Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia is the RIPE NCC (Réseaux IP Européens Network Coordination Centre).

IPv6 vs. IPv4

Even at first glance, it is obvious that the new address format of the sixth IP version differs significantly from that of its predecessor IPv4.

- IPv4 address: 203.0.120.195

- IPv6 address: 2001:0620:0000:0000:0211:24FF:FE80:C12C

While the IPv4 uses 32-bit addresses, which are usually in decimal presentation, its successor IPv6 uses 128-bit addresses, which are displayed in hexadecimal format for readability reasons. Direct comparison illustrates the central concern, which is addressed by the new IP standard: With 128 bits, significantly more unique IP addresses can be generated than with 32 bits.

- Address range of IPv4: 32 bit = 232 addresses ≈ 4.3 billion addresses

- Address range of IPv6: 128 bit = 2128 addresses ≈ 340 sextillion addresses

The difference in size is made clear by a comparison: While the address range of IPv4 with around 4.3 billion IPS is not even close to enough to provide every person in the world with a unique address, a 128-bit system can theoretically assign each grain of sand on earth several IP addresses of its own. The introduction of IPv6 can therefore be viewed as an investment in the future. Trends such as the Internet of Things (IoT) suggest that the number of devices that connect to the internet and need to be clearly identifiable will grow drastically in the coming years.

Construction of an IPv6 address

The 128 bits of an IPv6 address are divided into eight blocks of 16 bits each. In hexadecimal notation, a 16-bit block can be recorded with four digits or letters. The colon acts as a separation element:

- 2001:0620:0000:0000:0211:24FF:C12C

In order to make the IPv6 address more manageable, a shorthand has been established where leading zeros within hexadecimal blocks can be omitted. If a hexadecimal block consists exclusively of zeros, the last zero must be retained:

- 2001:0620:0000:0000:0211:24FF:FE80:C12C

- 2001:620:0:0:211:24FF:FE80:C12C

Once per IPv6 address, it is also possible to delete any consecutive blocks of zeros.

- 2001:620:0:0:211:24FF:FE80:C12C

- 2001:620::211:24FF:FE80:C12C

The consecutive colons (after the second block in the example above) indicate the omission.

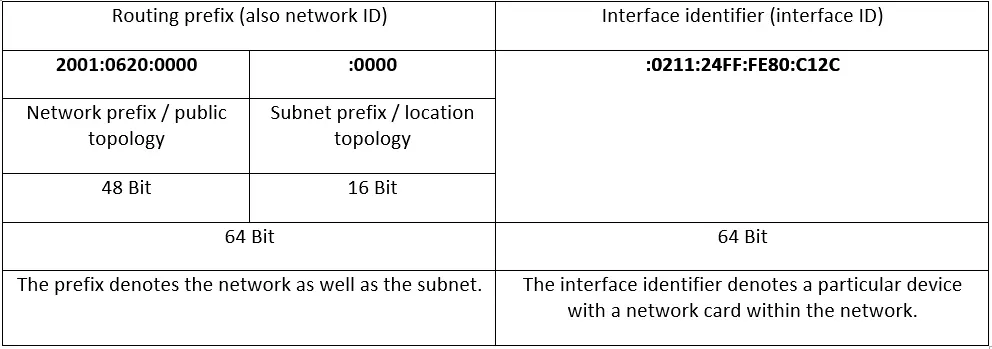

In reality, internet users have far fewer addresses available than the 128-bit format suggests. The reason for this is the design principle of IPv6: unlike the previous version, the new standard is intended to allow for real end-to-end connections and make the translation of private to public IP addresses based on NAT (Network Address Translation) unnecessary. In principle, end-to-end connections should be possible with IPv4 as well; however, since the IPv4 address space is too small to provide each device with a unique address, a system with separate address areas and the mediating component NAT were developed. With the new standard, any device that is connected to a LAN can be addressed logically via its own IP. IPv6 addresses therefore contain, in addition to the section on network addressing (also called network address or routing prefix), a unique interface identifier which either results from the MAC address of the network card of the device or is generated manually. The routing prefix and the interface identifier each comprise 64 bits of an IPv6 address.

Structure: Routing prefix

As a rule, the routing prefix of an IPv6 address is divided into a network prefix and a subnet prefix. This is illustrated in the so-called CIDR notation (Classless Inter-Domain Routing). For this purpose, the prefix length (i.e. the length of the prefix in bits) is affixed to the network address with a slash (/).

The notation 2001:0820:9511::/48 describes, for example, a subnetwork with the address 2001:0820:9511:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000 to 2001:0820:9511:FFFF:FFFF:FFFF:FFFF:FFFF.

Generally, internet providers (ISP) are allocated by the RIR /32 networks, which in turn arrange them into subnets. End users are given either /48 networks or /56 networks. The following table shows the typical construction of a global unicast address in IPv6 consisting of network prefix, subnet prefix, and interface identifier.

Structure: Interface identifier

The interface identifier acts as a distinct marking of a particular device which is connected to the network and is either assigned manually or generated based on the MAC address of the device’s network card. Typically it happens the second way, and is based on the conversion of the standardised MAC address into the modified EUI-64 format. This happens in three steps:

- In the first step, the 48-bit MAC address is broken down into two 24-bit pieces. These pieces become the beginning and the end of the 64-bit interface identifier.

- MAC address: 00-11-24-80-C1-2C

- Disassembled MAC address: 0011:24__:__80:C12C

- The second step assigns the remaining 16 bits in the middle by default to the bit sequence 1111 1111 1111 1110, which corresponds to the hexadecimal code FFFE:

- Completed MAC address: 0011:24FF:FE80:C12C

- The MAC address is now in the modified EUI-64 format.

- In the third step, the seventh bit, also called the universal or local bit, is inverted. This specifies whether an address is globally unique or is only used locally.

- Bit order before inversion: 0000 0000

- Bit order after inversion: 0000 0010

- Interface identifier before inversion: 0011:24FF:FE80:C12C

- Interface identifier after inversion: 0211:24FF:FE80:C12C

Privacy extensions

An IPv6 address based on the modified EUI-64 format allows for conclusions to be drawn from the underlying MAC address. Because this could cause privacy concerns for users, Privacy Extensions developed a process that allows IPv6 to make an interface identifier anonymous by removing the link between the MAC address and the interface identifier. Instead, Privacy Extensions generates a temporary interface identifier for outbound connections that is more or less random. This makes conclusions about the host and the creation of movement profiles on the basis of the IP more difficult.

IPv6 address types

As with IPv4, IPv6 contains different address areas with special tasks and properties. These are specified in RFC 4291 and RFC 5156 and can be already be identified by the first bits of an IPv6 address, the so-called format prefix. The central address types include unicast addresses, multicast addresses, and anycast addresses.

Unicast addresses

Unicast addresses are used to communicate one network element with exactly one other element, and can be divided into two categories: link local addresses and global unicast addresses.

- Link local addresses: Addresses in this category are only valid within local networks and begin with the format prefix FE80::/10. Local link addresses are used to address elements within a local network and are used, for example, for auto-configuration. In general, the scope of a link local address extends to the next router, so that any device connected to the network is able to communicate with it to generate a global IPv6 address. This process is called neighbor discovery.

- Global unicast addresses: Global unicast addresses are worldwide unique addresses that a network device needs in order to connect to the internet. The format prefix is usually 2000::/3 and includes all addresses that begin with 2000 to 3FFF. The global unicast address is routable and can be used to directly address a host in the local network over the internet. Global unicast addresses, which are redistributed from internet providers to end users, begin with the hexadecimal block 2001.

Multicast addresses

While unicast addresses are used for one-to-one communication, multicast addresses implement a one-to-many communication. Along with this come distributor addresses. Packages that are sent from a multicast address are received by all of the network devices that are part of the multicast group. One device can belong to multiple multicast groups. If an IPv6 address is created for a network device, then it is automatically a member of certain multicast groups that are required for recognition, accessibility, and prefix detection. Common multicast groups, for example, are “all routers” or “all hosts”. The format prefix for multicast addresses is generally FF00::/8.

Anycast addresses

Packages can also be sent to groups of receivers from anycast addresses. Unlike multicast addresses, though, data packages are not sent to all members of an anycast group, but only to the device closest to the sender. Anycast addresses are used primarily for load distribution and failure safety purposes.

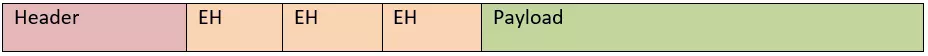

IPv6 package format

Compared to IPv4, the internet protocol v6 is characterised by a significantly simplified package format. To simplify processing for IPv6 packages, a default header length of 40 bytes (320 bits) was set. Optional information that is only needed in special cases was outsourced to extension headers (EH) that are embedded between the header data area and the actual payload. This allows options to be inserted without requiring change to the header.

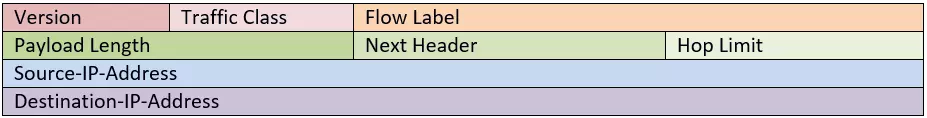

The IPv6 package header only contains eight headers – with IPv4, thirteen fields were used. The structure of an IPv6 header can be represented schematically as follows:

Every field in the IPv6 header contains certain information that is required for package transfer over IP networks:

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Version | Contains the version of the IP protocol according to which the IP package was created (4 Bit) |

| Traffic Class | Denotes the priority allocation (8 Bit) |

| Flow Label | Packages with the same flow level are treated the same way(20 Bit) |

| Payload Length | Specifies the length of the package contents, including extensions, but without header data (16 Bit) |

| Next Header | Specifies the protocol of the parent transport layer (8 Bit) |

| Hop Limit | Specifies the maximum number of intermediate routers a package may pass before it expires (8 Bit) |

| Source-IP-Address | Contains the sender address (128 Bit) |

| Destination-IP-Address | Contains the recipient addresses (128 Bit) |

The introduction of extension headers makes it possible to implement optional information in IPv6 packages much more effectively than with IPv4. Because routers on the delivery path of a package neither check nor process IPv6 extension headers, these are usually only read at the destination. This results in a significant improvement of router performance in comparison with IPv4, which required that optional information be examined by all routers along the delivery path. The information that could be included in IPv6 header extensions includes node-to-node options, destination options, routing options, and fragmentation, authentication, and encryption options (IPsec).

Functionality of internet protocol version 6

Most internet users are connected with IPv6, mostly due to the expansion of the address space. However, the new standard also provides a number of features that can overcome the key limitations of IPv4. Above all, this includes the consistent implementation of the end-to-end principle, which makes the detour via NAT superfluous, simplifying the implementation of security protocols such as IPsec.

Additionally, IPv6 enables automatic address configuration via neighbor discovery as well as allowing multiple unique IPv6 addresses per host with different scopes to map different network topologies. In addition to the optimised address assignment, the simplification of the package header and outsourcing of optional information to header extensions for package transfers ensures faster routing.

With QoS (Quality of Service), IPv6 has an integrated mechanism for the security of quality service which prioritises urgent packages and makes package handling more efficient. The fields “traffic class” and “flow label” have been directly tailor to the QoS methodology.

Critical to consider, though, is the assignment of static IP addresses to local network devices, as well as the practice of creating unique interface identifiers based on MAC addresses. Privacy extensions certainly created an alternative to the modified EUI-64 address format; however, because the prefix of an IPv6 address is also sufficient to create a user’s movement profile, a new prefix that is dynamically assigned by the ISP for maintaining anonymity on the internet would be desirable in addition to the privacy extensions.