PTR record: How does the DNS record work?

The domain name system (DNS) simplifies online communication. Its most well-known function is probably name resolution. This enables a user to enter a URL in the browser and still establish a connection via an IP address. For this to work, the DNS, or more specifically, the responsible name servers, access the zone files. These are simple text files in which DNS records are listed line for line. At the same time, name resolution is performed via A records or AAAA records. E-mail connections are enabled with MX records.

The DNS recognises more than 100 different types of resource records. In our overview article on the various dns record types, we have listed all record types and provide a brief description for each one. Plus, you can also learn more about the basic principle behind DNS records.

PTR records effectively constitute the counterpart to A records. Instead of assigning a domain name to an IP address, the link occurs the other way around. In this way, PTR records make reverse DNS possible.

PTR records explained with an example

PTR stands for “Pointer.” The name already gives you an initial idea of what is achieved with the record type. A PTR record refers to an object: the domain name. This makes the reverse DNS (rDNS) or reverse lookup possible. Typically, a user would like to establish a connection to a server with a domain name that’s already known, but they do not have the correct IP address. In the case of a reverse request, the process occurs in the exact opposite direction: The IP address is already known and the user wishes to find out what the appropriate domain is called or under which URL it can be reached.

Record syntax

A PTR record’s structure is similar to that of the other record types. The various pieces of information are arranged in the record one after another in fields.

- <name>: The first field in the PTR record is filled with the IP address

- <ttl>: The time to live specifies the time in seconds that an entry is valid for, before it needs to be activated again

- <class>: This field contains the abbreviation of the network class being used

- <type>: In this case, PTR is located in the fourth position in order to define the record type

- <rdata>: Finally, the last field contains the resource data – the domain name

All fields are arranged according to the sequence within a line. The fields are not separated by a symbol; a space is sufficient. The line and hence the record are only ended through the use of a line break.

<name> <ttl> <class> <type> <rdata>The syntax is structured exactly as it is in an A record, only the field content is different. Initially, the IP address is specified. For this, both the IPv4 and IPv6 addresses are valid. But there is one special characteristic to keep in mind: reverse mapping is used here. The IP address is therefore specified in reverse sequence.

If using an IPv4 address, however, it only involves octets. Within the specific groups, the serial number sequence remains unchanged. It is different with IPv6 addresses: With them, each number and/or letter is reversed and separated from the next value with a full stop. Even leading zeros, which are normally omitted in hexadecimal notation, are written out in PTR records.

The zone also has to be specified. Here, there are two that are possible, again depending on whether an IPv4 or IPv6 address is concerned. The former receives the extension in-addr.arpa., the latter ip6.arpa.

PTR records, like all other DNS records, use fully qualified domain names (FQDNs). This means that the domain names (both in the name field and in the resource data) always end with a period. This separates the top-level domain (TLD) from the root directory, which is nevertheless represented as an empty field.

The time to live specifies the duration that a record is still valid for. If the time period has lapsed, the information has to be requested again. This way, the DNS avoids the problem of having possibly outdated records held in the cache, which can then lead to connection issues. Usually, however, this field does not appear in the record itself. Instead, with the directive $TTL at the beginning of the file, time is determined for the entire zone. The TTL is specified in seconds.

Today, the class field is only of historical significance. When the DNS was being developed, there were still two other network projects: Hesiod (with the abbreviation HS) and Chaosnet (represented by CH)). Both are no longer used, which is why only internet is possible for the class. For this reason, this field normally contains the abbreviation IN or is completely omitted. When left blank, the system is based on the usual standard, which in turn is the internet. For this kind of record, the type is understandably always PTR. In the final data field, the domain name can then be found – again in FQDN notation.

Example of a PTR record

As an example, let’s assume that a user knows example.org’s IP address, but doesn’t know which domain is behind it. The address reads 2606:2800:220:1:248:1893:25c8:1946 and 93.184.216.34. In order for the user to use reverse DNS, we make PTR records available. These would then be structured the following way in this example:

$TTL 2100

34.216.184.93.in-addr.arpa. IN PTR example.org.

6.4.9.1.8.c.5.2.3.9.8.1.8.4.2.0.1.0.0.0.0.2.2.0.0.0.8.2.6.0.6.2.ip6.arpa. IN PTR example.org.Here, we have determined the time to live at the beginning of the file so that it is valid for all records. Both PTR records then follow, each containing the IP addresses referencing the domain names. These enable the reverse lookup.

Looking for an alternative to the traditional .co.uk extension, or want to grow your online presence? Give .uk a try today.

£1 for 1 year!

PTR record lookup: How to check the record

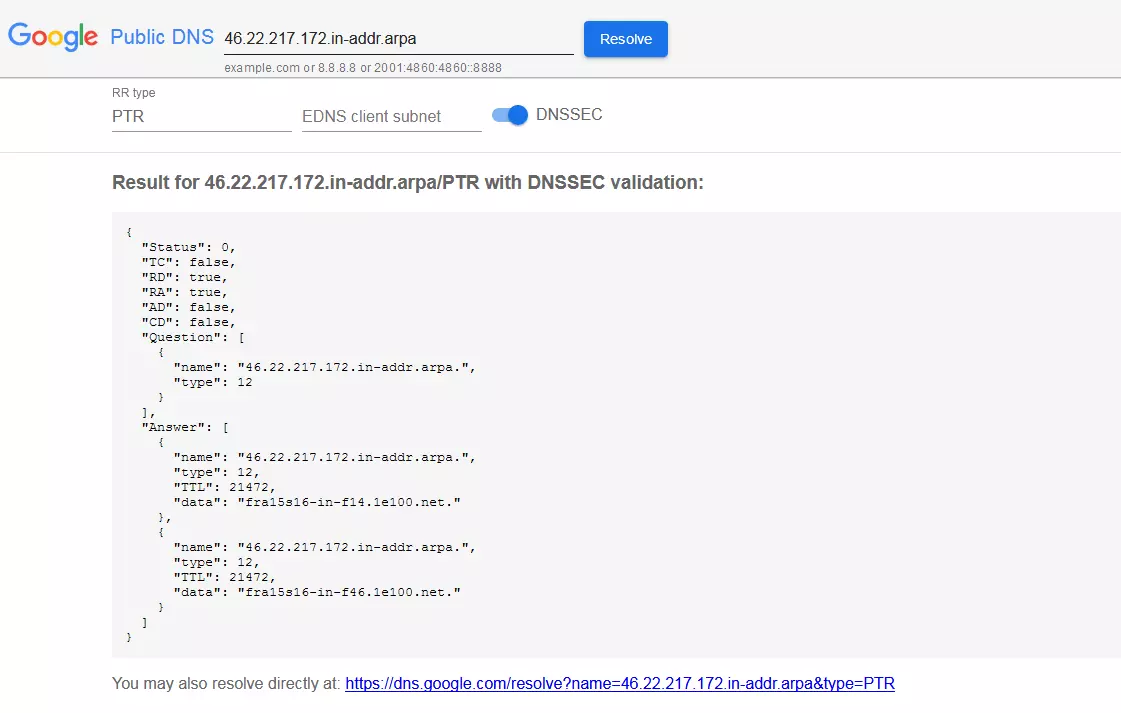

If you want to see a website’s PTR record, you can use a number of web services to do so. With Public DNS, Google offers users the option of having all of a domain’s available DNS records displayed. In order to activate the PTR record, you enter a valid IP address on the service’s website. It is not necessary to convert the address so that it complies with the PTR record format. Google’s application takes care of this itself.

Public DNS should automatically recognise that you would like to perform a PTR record lookup. Both the EDNS Client Subnet and DNSSEC configuration options need not be changed. The first option enables a more efficient DNS request and the second guarantees that no third party has intercepted the line of communication and changed the requested information.

The results appear under the “Answer” item. The service immediately provides two different servers whose names can be found under “Data.” As you can see, both have the same value with respect to the TTL, which indicates an allocation for the entire zone.

For type, you’ll find a number instead of an abbreviation. The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) has given each record type an individual value, assigning each of them a serial number. The PTR record is associated with the number 12.

The verified IP address is actually part of the google.com domain. The answers, however, point directly to internal server names that are not for public use and also don’t function as URLs.

Anyone who doesn’t want to use the Google service also has a number of other options available that enable a PTR record check, such as DNS Check, dnsqueries.com, and ptrrecord.net.